Ever since he became British prime minister a little over a year ago, Rishi Sunak has tried to bring calm to the chaotic government he inherited.

His predecessor Liz Truss’ economic policies had caused the pound to fall to its lowest level against the dollar in decades. Inflation was in double digits. Interest rates were rising. And his governing Conservative Party was still struggling to recover from the turmoil of Boris Johnson’s premiership before Truss – which ended in scandal, public fury and dreadful poll ratings.

Despite his aim of steadying the ship, Sunak has struggled to tell a convincing story of exactly what his political personality is and to which brand of Conservatism he belongs.

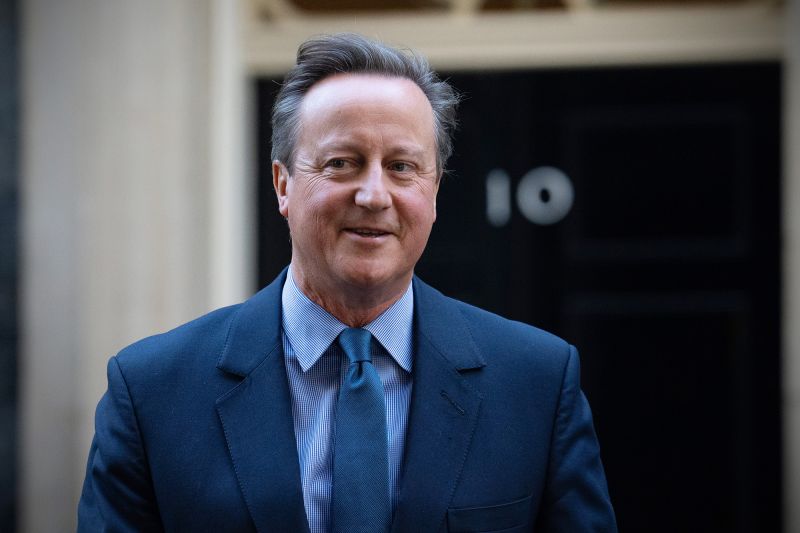

That might all have changed on Monday when Sunak surprised the Westminster establishment by appointing former Prime Minister David Cameron as his new foreign secretary. He did so after sacking Suella Braverman – a firebrand from the right of the party who recently described pro-Palestinian demonstrations as “hate marches” and called homelessness a “lifestyle choice” – as home secretary.

Cameron, of course, is best known as the PM who called the in-out Brexit referendum of 2016. He was very much from the center of the Conservative Party and led the campaign to remain in the European Union. The UK’s subsequent shock decision to leave the EU led to Cameron’s resignation on the morning of the result and kick-started seven years of bitter, partisan politics among Conservatives over Brexit and, to some extent, the soul of the party.

Almost overnight, Cameron’s pro-green, pro-social reform, centrist liberal Conservatism was thrown out the window, leaving a massive space for people on the right, like Braverman, to shift the whole party in their direction.

Conventional wisdom had been that Sunak was too weak to sack Braverman, even though she had been speaking out on controversial issues for months and had, most believe, been laying the groundwork to replace Sunak should he lose the next election.

Many also believed that keeping Braverman in a key cabinet post was primarily about party management and appeasing the right of his party who privately suspected Sunak to be a closet liberal.

The appointment of Cameron and sacking of Braverman might suggest to those critics that Sunak is finally showing his true colours and throwing his lot in with the moderates – thereby distancing himself from the culture wars and tub thumping of Johnson, Truss and, indeed, Braverman.

Pulling his government back to the center might seem sensible, since the Conservatives’ poll numbers remain dire and the public at large seems tired of tumultuous politics.

But he will need to square it with his own party, which won’t be easy as Conservative MPs, members and voters remain divided into numerous factions.

Some love the populist, culture war politics of Johnson and think forcing him from office has already cost the Conservatives the next election. Others are low-tax libertarians. On the right of the party are a group who want a hard line to be taken on criminals and immigrants. And on the left of the party are the moderates, who think the public is sick of the Conservative psychodrama and want to return to mature government.

Sunak has to some extent tried to be all of these things over the past year, while also painting himself as an agent of change who isn’t defined by the past 13 years of Conservative government – in which he served as finance minister.

It was only last month he addressed the Conservative annual conference and criticized the past “30 years of a political system that incentivizes the easy decision, not the right one.”

In that speech, Sunak endorsed harsher sentences for criminals, defended a U-turn on the UK’s green transition, made dismissive comments about trans rights and gave a rousing endorsement of Braverman’s plans to have refugees deported to Rwanda – something British courts have prevented the government from doing. It’s a bit of a mystery how a shift to the center and Cameron fits into all this. He was, after all, one of the many previous leaders from whom Sunak has tried to distance himself.

Cameron comes with a lot of baggage.

First there is Brexit, which he, in the eyes of his critics, allowed to happen by calling the referendum, convincing his fellow world leaders that the remain side would win – then immediately quitting after losing. Many in British politics have not forgiven him for this.

More recently, he was caught up in a lobbying scandal in which he personally lobbied Sunak, then Johnson’s finance minister, to secure government funds to prevent a financial services company he worked for from collapsing during the Covid-19 pandemic. His requests were denied.

By some on the right of the party he is viewed as the enemy. Before becoming party leader in 2005 and PM in 2010, Cameron was a modernizer.

Shortly after becoming party leader in 2006, he gave a speech suggesting that young people who wore hoodies shouldn’t be feared, but shown more love. He was also pictured hugging huskies in a drive to prove his green credentials.

From 2010-2015 he governed in coalition with the centrist, pro-European Liberal Democrats. Many of his more right-wing MPs believed Cameron to be more at home with the Liberal Democrats than what they saw as real Conservatives.

The appointment will continue to raise more questions over the coming days as observers watch for any discernible changes in government policy or nods to a centrist pivot. It is hard to even know exactly how Sunak could do that – it was only last week his policy agenda, containing many right-wing positions, for the coming year was officially laid out in parliament. Similarly, it’s not as though Sunak was unequivocally of the right before this. He cannot pivot from one position to another when he hadn’t previously been convincingly one or the other.

But as the election, mostly likely to happen at some point next year, draws closer, maybe the finer points of governing don’t actually matter. Maybe this is more of a general vibe shift: bringing in a safe pair of hands to demonstrate stability to the voters while keeping harder-line policies in the manifesto to keep his Conservative critics off his back.

Whatever the truth behind Sunak’s unorthodox reshuffle of his top team, he doesn’t have long before it needs to start having an impact on his political fate. The next election is looming and his party is still a long, long way behind in the polls.